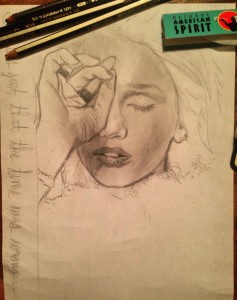

untitled | charcoal, #2 pencil, and HB and 6B graphite | july 16, 2016

Page 2 of 3

Let it pass: April is over, April is over. There are all kinds of love in the world, but never the same love twice.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Sensible Thing

This year passed through my mind like cyanide. At times, I could feel myself breaking apart. Every movement smarted and seared, but the burning part of me was dim. My skin was vivid with bruises: deep, nebulous blues and stretches of diseased yellow. I feared that I would crumble at the touch.

Weary to the point of half-etherized surrender, each joint infected with a soreness like desire, I would try to sleep and find myself unable to escape my own lucidity. I was so awake, so damningly conscious, driven well past the point of endurance. I could feel the incessant, maddening cadence of my heart, racing like a hunted animal, enervated yet brutally alive.

My undertaking was not finished. There was work to be done. My body was a ritual sacrifice, but I was no martyr, not even close. I was something dispensable: somatic and inclined towards agony. Twice-deceived idolatress or Judas’ child, inadequate priestess or false savior: it seemed that though I suffered, no one healed. My immolation was futile, unfinished, but I offered it all the same. My world was a crematorium, flooded with smoke and unheard prayers, not fifteen paces from the stained-glass houses of my childhood, where I used to believe I felt the presence of God.

I took refuge in one who bore steadfast witness to the tides of this truth that might have drowned her. I wrested some sort of shelter from that faithful, forlorn thing: I was the catastrophe from which she would not avert her eyes. I passed the unwelcome time by teaching myself, gradually, assiduously, to love her, until it became became feasible, and then habitual, and then inescapable. What a feeling, her fragile form, and how she looked at me, dark eyes alight. I knew my name as I never have before when it fell burning from her mouth like a prayer.

At times own memory evades me, trickles away like rainwater on panes of frosted glass, a consequence of choices that still take my breath away. But I will always remember fondly the nights of my near-resuscitation, each promise of renewal, those words that tethered my soul to her body in tides of empathy and admission. The gentle hands, as they moved across the strings—like Camelot, Troy, and Pandæmonium before us, that world of ours was built to music.

There were times when she would sleep and I would write well into the dawn, filling that room with growing things: lotus boughs and reams of ivy, garlands of juniper and night-blooming jasmine. They blossomed in that darkness, and so did I, my body opening and unfolding until the space became a garden of my own design. I watched an ash tree grow through our bed, rooted in the soils of a history we constructed, and knew the joys of some new genesis of the body. I gave life to my self and my longings once more, and when the morning rang with the bells of the city, I stood on the rooftops and saw a possible world take form.Threatened with the specter of inevitable expulsion, I endured. My nights lingered sweetly in charcoal impressions of her skin, until what we created became a kind of folklore: crystallized and bound to its irretrievable past.

I left everything behind me. It is so often said or desired, but I really did it. I put an ocean between myself and the history I despised. I remembered and wrote and reimagined until there was nothing left that I knew except for myself. And what a time it was. If those months did not not break me, I doubt that there is anything that can.

Now, my blood and my conscience are finally clean. I have faced a kind of hell, and though I am changed, I am yet living. How many others can say the same? I am carving a new and better space for it, for me, this writer-user-lover-addict, imprecise and genderless and never meant to survive. Lazarus form, Tiresian mind, Electra heart, Orphean soul—still lost, sometimes living, I shatter on. I am Icarus in flames, my burning body a testament to another’s failures. I am nowhere close to apologizing.

Someday I will write, in full, the history of this form: in gradients of desire and each forgotten cross I have climbed. I will give a language, at last, to the absence that breathes and burns within me, to the specter of my wordless story, and to the child I cannot mourn. I do not know where it is taking me, this body that atones. But I am the center that holds.

I know that I am not entirely well yet. To heal will require time. Survival is the art of accepting nothing more or less than your own continued existence—and so I have always lived like this, because I knew no other way.

What will I become, once I am no longer content to merely survive?

Am I still lost?

Once I was beautiful. Now I am myself.Anne Sexton, To Bedlam and Part Way Back

Winter is finally ending. Months passed and I failed to notice. My mind inverted, folded over on itself, inexplicably sought to reopen this history that resists like a cauterized wound. I have spent my days striving in vain to name a need beyond the limits of language: something shrouded in opaque desire and the wordless things my body used to know.

These days, I am not sure where I stand. When I medicate my exhaustion, the elation feels fractured, like splintered glass beneath my skin. Laughter weighs on me: I wear happiness like a vice. I write and I smoke and I read and I wonder, I move from one life to the next without registering the difference. I am a thing apart from itself.

You might think that such a state would, if nothing else, engender art. But if I am being honest, I have seldom felt less inspired. The world is closing in around me, and I am left stationary, without interest or intention. I wonder what sacrifices I am making, without the slightest knowledge of their consequences.

While so much of my recent existence has been a concentrated movement towards apathy, there were moments when I felt everything, and it hurt. I learned something close to love for a person who knew how that felt. Whatever else happened, he tried, and that was something beautiful. It took me months to realize what tenacity and care must have gone into those efforts to know me in a world he could barely survive. I wish that we had found each other in some other place and time, when I could still love, and he could still remember, and the past did not weigh like a nightmare on our minds. I will write our eulogy for years to come.

And I have been so lucky in so many ways. I encountered a woman more passionate and more pure than I believed possible, and at whose hands I knew an ecstasy almost past endurance. I found a man who spoke my name like it mattered. I met living things whose bodies defied simple classification and momentary lovers who knew no gender at all. Those nights were radiant in their own strange ways, the mornings insouciant and sanguine.

So, there have been moments of respite and invaluable connection. Mostly, though, there has been a sense of absence: a chasm of negative space that carved its way through weeks and months of existence. I am so alone that it scares me. I am so reluctant to admit how self-reliant I must become. I want to believe that there is still some person, or some place, or some purpose, that might sustain me indefinitely.

Briefly, and by sheer virtue of coincidence, I found a source of imperfect solace. It never felt beautiful until I knew that I would lose it. On our last night together, I remained awake well into the dawn, not moving, not speaking, just holding his sleeping form.

For an instant, I nearly understood him: the angular profile, the pierced ears, the quick, unconscious movements when he shifted in his sleep. I raised myself on one elbow. One of my hands was in one of his: he always held it when he slept. With the outstretched fingers of the other, I traced the profile of the extraordinary being who had accompanied me in my efforts to revive a ruined body. I wondered if he had already faded beyond my recollection. I wondered how or why that had come to be. I wondered, as I often have lately, how I became so callous and self-contradicting: too withdrawn to remedy my own isolation, and too afraid to care. I never wanted to leave that room—but when I awoke and he was gone, I felt nothing. I smoothed out the imprint of my form from his sheets. I took every trace of myself and walked out the door. And that was it.

The act of losing something is seldom determined by physical presence. We engage with loss, in its purest form, when we can no longer sustain the illusion of vitality: when we accept, without question, that an ending of sorts has begun. I hope I did the right thing. I do not want to believe that this was without meaning. I like to think its roots were deeper, more singular, like the last thing he said on the first night I knew him, and the words we exchanged in the darkness thereafter.

I do not want to be exhausting, unpredictable, volatile, extreme. I want to be something closer to normal. I want to be amiable and easy and at peace. But I also want to burn. I want to consume and linger on forever. I want to live with such spectacular finesse that if the world were to end in fire, you would know by whose hand it fell. It is mad, but not complicated: I want to be more than this body. I want to relinquish its past and its pain. I hate being tethered to a thing that bleeds so easily.

I like to think that I was born with chaos in my soul, a descendent of all of the witches that the world could not find fire to burn. Maybe that is why my body turns feral, why my sanity slips into paradigms of unreality and converses there with itself. I like to think that I am as potent as she was, my fallen companion and second self, who taught me astonishing, terrible ways to feel like a living thing and then left me with nothing at all.

But I am more and less than she is. I could not survive my own inclinations, and so the winter reduced me to madness once more. The world was harsh, the sun was bright, and the people were terrifying and desirable. So, I had to keep moving.

I went to a place where the streets seemed less foreboding, with half a pack of cigarettes and two people I love. I thought that the anonymity of a new city might heal me. I tried, and maybe it helped. At any rate, I started to breathe again. I tried to view that city in all of its vibrancy and motion, tried to understand what one man must have felt when, wandering the fields of Provence, he saw the evening sky in paradigms of ecstasy. I found clairvoyance in quiet canals and the light that fell across their waters. In darkened shops I paid for respite, using burnished foreign coins like the ones my father kept in the shallow dish by his black office desk—my father, who travelled to faraway places, who I loved more than my life, myself.

I have said it before, but I love without direction or purpose. And if it seems careless, or casual, or inane, that is only because I strive too intently for neutrality. I fear the sensation of being loved and left. I am obscenely well versed in impermanence and untruths.

But once again, in spite of my own best efforts, something in my subconscious stirs. It is roused and vaguely searching, enraptured by a desire to which it is too wary to ascribe any semblance of language or form. This vague potentiality is nothing new, nothing peculiar: it is one of the earliest memories that I have. Beneath the surface, like a dream upon waking, like memories images that linger in a sober mind, he is never really present and never fully gone. His was the figure upon which my clandestine desires took their most inexplicable forms.

Some acts of destruction lack a name. These impulses may lead nowhere at all.

This is a violent fucking world—never let anyone tell you otherwise. I have spent too long pretending that there will ever be any sanctuary other than that which I provide for myself. I have wasted years trying to justify my existence with the promise of some better person or place. I no longer wish to know the futility of this feeling. Someone told me once that my writing will always be too abstract for anyone to really read it. So I will speak, for once, as plainly as I can. Maybe it will make the difference. Maybe someone will hear me.

Be honest. Be direct. Is this beautiful yet?

I don’t fucking care anymore. Is this beautiful yet?

I am defiant. I am surviving. Is this beautiful yet?

Don’t breathe too deeply, or you start to feel it hurting. Don’t remember too fondly, or you will forget to live at all. Don’t stay too long, or you’ll remember why you loved her in the first place.

Don’t apologize. Don’t think. Don’t need things that people can’t give you.

Desire shamelessly. Engage recklessly. Love absurdly. It is the only thing worth living for—so let yourself feel this way again, and again, and again.

Is this beautiful yet?

Am I beautiful yet?

Or am I merely something new?

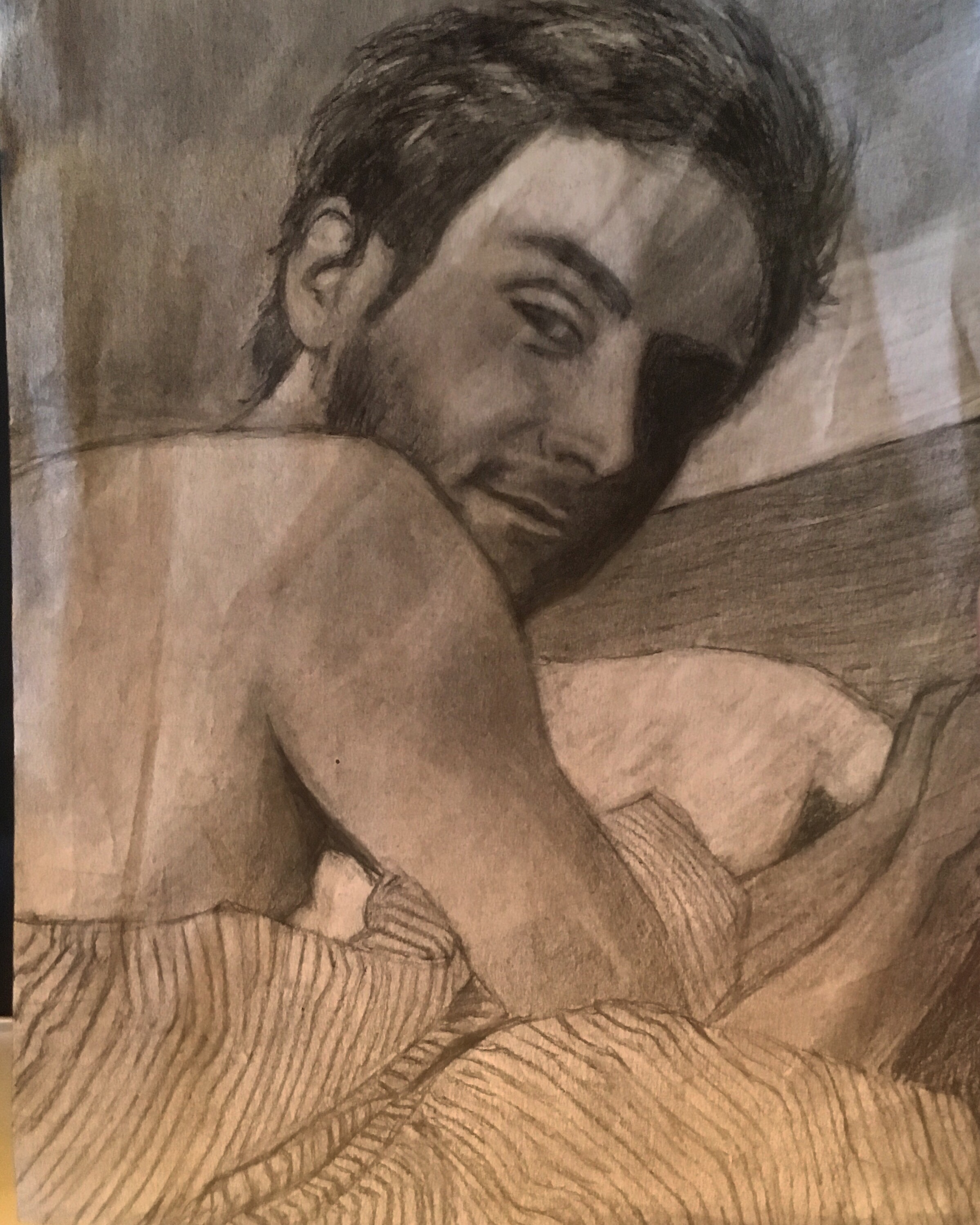

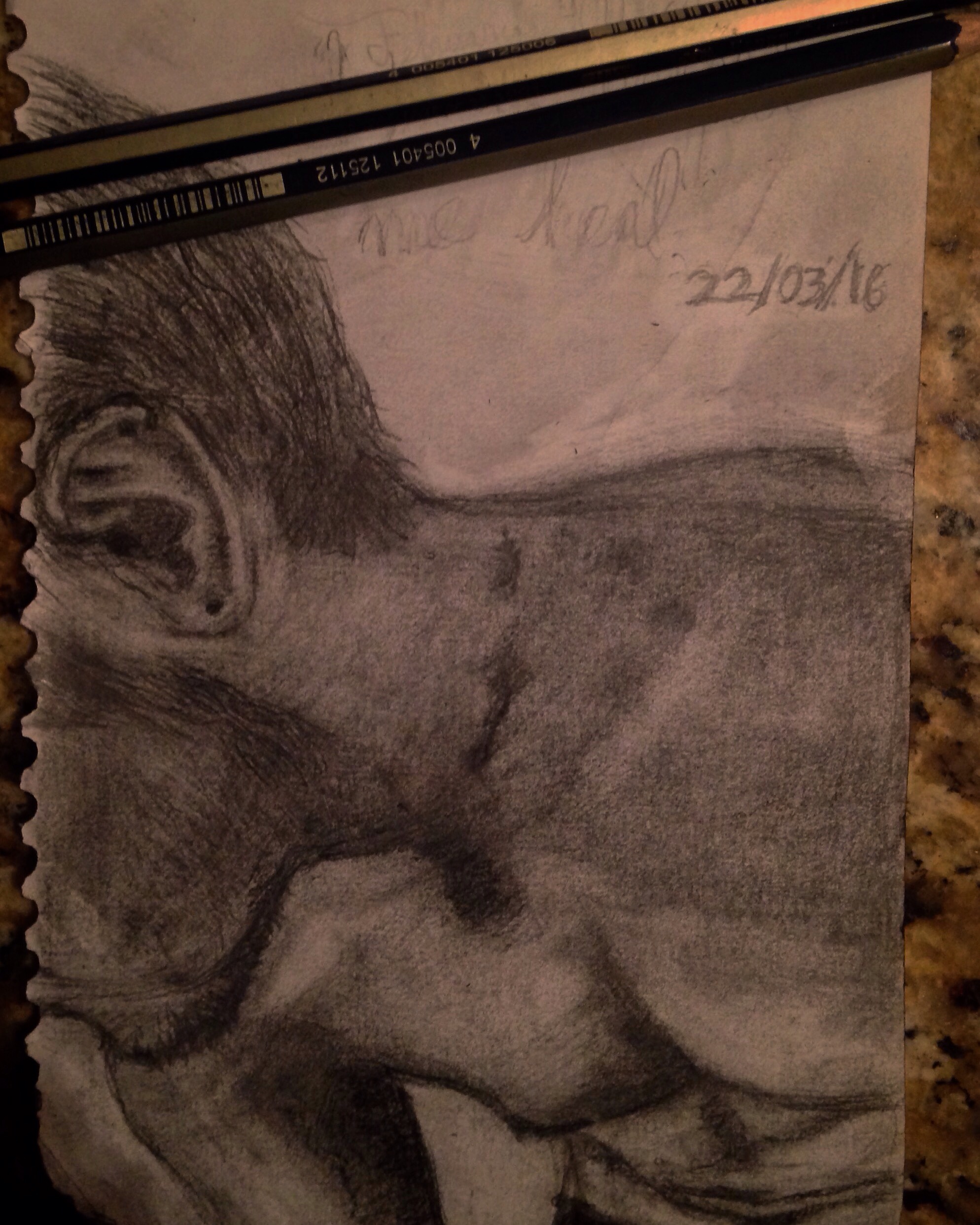

“those strange early days” | charcoal and #2 pencil | march 2016 | unfinished

It is the difference between planetary light and the combustion of stars.

E.B. White, The Ring of Time

Currents of ink move in and around me. I lie still. Back arched, shivering, my eyes trace shadows across the mirrored ceiling. Some nights are easier than others. In shades of masochism, I disallow pleasure. I am not in agony, not exactly, but I am nearing it. My mind, like my body, resists its own desires. It is the final refuge of a form that has been wounded time and again.

But then I feel my own self move: the yearning and warmth, the vulnerability and vanity, and some of the trauma bleeds out and away. I awake bearing bruises that span my form like constellations, whispering nebulous patterns across my skin. The pleasure is so simple, so profound: to allow someone to love me, to feel affection on the surface when I cannot respond in full

Enticed by the presence of each new fascination, I have experienced these weeks in subtle variations, like music changing key. I am affected, intrigued, burning softly—but this will not destroy me. And how futile, how tedious that can feel.

Is it possible that this is the better way of feeling and creating? The pain of the last ending was damning, even for me. We were wasting my final cigarette on a poorly lit street when, without warning or provocation, my mind engaged at last with the full ramifications of my wasted time. I watched the dispersion of ash across his fingernails, and desired suddenly to shake him, to scream, Meet my eyes. Say my name. You’re fucking empty—

But how was he meant to have appeased me, being so undone in his right? The answer emerges in its own futility. I never wanted to be appeased. I wanted to thrill him, to hurt him, to make him feel everything I no longer wanted to. I wanted to tear him apart and work my way inside of him, lace my fingers through the notches in his spine, pull the skin away and expose the bone. I wanted to dissemble him, that poor desperate thing, and breathe some sort of life into whatever remained. I wanted to punish and save him. I wanted to play God. I would do better to learn my own value than to love like that again.

But then, maybe that is not the whole truth of it. Maybe it was simpler and less cruel. Maybe I really did recognize something of myself in that gentle and disarrayed mind. Maybe I just wanted to love something—to love anything at all.

But in the margins of my lucidity, his image haunts me still. Not even a week ago, as I lay in the arms of the woman who had shared my bed, I dreamed of him. I was awake while I was dreaming: that was the most frightening part. But it was dreaming all the same, and no less for my sentient state. I was conscious but not present, somehow. He was walking down an empty street, his hands in his pockets, younger and less marred by circumstance. I knew at once that he must have died to have been rendered so complete. There were no secrets to draw back from, no lies left to tell: I felt no pain and his eyes seemed like the morning to me once more.

But fortitude is an exercise in self-denial. So I left the sleeping girl where she lay, her long hair strewn over her shoulders, her raised scars gleaming in the early light. Kneeling beside her cluttered bedroom table, I cast myself again into that cold, clean state to which I have become so partial: the lucid currents that flood my veins like shards of glass, setting my teeth on edge, making me feel as though I could set my past on fire and walk away without a word. But a history like mine does not burn easily. It smolders like flesh and it festers, but it never really fades.

Eight months ago, in late summer, I shared cheap vodka, stale cigarettes, and the sunrise with a person I had met just hours previously. In the haze of not-quite-morning, I felt like I knew him as well as I have ever known another living being. I cannot recall what fear or desire I must have expressed, but a response fell from his mouth with such simple conviction that I have remembered each word ever since.

“You can’t seem to be anything other than what you are—you’re so you—and it’s funny, and it’s admirable, and it’s sad, and people are going to put you on a stage because they won’t know what else to do with you. And you’re going to have to be strong because of that.”

In the time that followed, I hardly knew what to make of that strange, blunt assertion. But now I can admit there was some truth to it. Childhood was wasted on me: I was always melancholic, always peculiar. People noticed and made me feel different. I never wanted to feel different.

How could I ever be anything other than what I am? Who would ever let me? I have loved recklessly. I have bled deliberately. Whatever my own mind has done to me, whatever it is doing, it provided solace when nothing else could. Were I anything other than what I am, I would be nothing at all.

In the early months of winter, in the a sunlit room, I found something close to happiness. I loved that time so effortlessly and entirely: it was sweet, and it was clairvoyant, and it should not have ended so soon. I wish I could have stayed just a little while longer in the sanctuary of four walls, where I was wanted and unafraid.

But there is no place for me there anymore. The waking world intervened, turned that sanctuary into another facet of my perverse effort towards self-portraiture. Once again, I am watching something die, something that I cared for, and I am powerless to save it.

I cannot sustain tender, or gentle, or vulnerable things. I am too violent, too defective. I burn with spectacular precision, but I cannot live simply or decently. I feel like I am not getting older, just growing weary as I watch the same cycles take new forms. I know that something left my life, but I do not understand when or why. So what does it matter anyways, this time around? This is not new to me: it will never be new to anyone who is only desired in their abstraction. Fissures appear, the glamour fades. I have lost beautiful things before, and I will lose this too.

I am everyone and no one, always running, always remembering, always trying so hard to not want to die. I have to keep moving: I cannot stop. Egoism, self-loathing, and profane fascination imbue all of the people that I am and have been—the withdrawn adolescent with open wounds and faraway eyes, retreating always towards an empty doorframe; the reverential lover of those bright and shining forms, wielding elation like a knife’s edge and leaving the image in their skin; the jaded user who medicates each memory, drowning an indifferent soul in chemical tides; the lost little girl who still cannot quite understand where her father has gone, or why.

My desperation ebbs like a pulse. I feel again the yearning of the child I was never allowed to be: to keep so quiet that no one can never find me. But the nostalgia is futile. I mourn for a past that is not mine. I am growing so weary of solitude and self-protection. I am ready to feel some other way.

My mind is tangled in bloodstains and bed sheets: in the refuge of a nameless language and the longings of a body altered long past recognition. Even after all of these years, there are parts of me that are not getting better. This is not a meditation: it is a confessional verse. People like me are not meant to survive. What does it mean for us when we do?

There will be time to murder and create.

T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

I found you in the edges of forgotten calamity, the hunting call of winter. I had been cynical and listless and tired and you made me feel new, like morning. I was reckless, when I should have been wary. What I mistook for love was nothing more than the reflection of my vanity, an exercise in self-gratification. Tenderness dims into delirium. I have nothing left to give.

A caustic want breathes beneath my reason, recalls an abandonment I may never exorcise. It festers and compels my form, like richness in the soil. Can you feel darkness, when you move in me? Is it why you draw back, then closer, imitating tenderness when you wish to tear skin back and bare subtle bone?

E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stele, witness your expulsion from my form. You were a long-term causality. You were an unfolding catastrophe. The body you destroy is your own. I exhaled you like a constellation, you feral thing.

I will be there when the tides roll back, to linger and recall this lost potentiality, this stillborn love that died before taking form. This, of all things, is my cardinal sin: I cannot keep life alive. I am not fertile, not whole. My empathy is not a virtue, but a willingness towards mutilation. I am deficient. I am empty. I allow things to die.

In chemical currents of wretched somnambulism, I evoke a wasteland that has yet to come into being. Every woman was born to wrest stars from their galaxies, to grapple with the voiceless language that floods the margins of sensation, when ecstasy moves through the body’s breathing core. In the still-living darkness of my sanity and soul, have been birthed for this purpose. I occupy that liminal position between the tangible and the untrue, my memory colored by the fantasies and phobias of a thousand other minds. A sentience moves through my androgyny and my desires, caves the space for a nameless gender.

Two years ago, the waking spring told different stories of this same conscience. Even now, I cannot write or speak candidly of that time: it is too shameful, too obscene. When the fourth morning dawned, its pale light found me upright, enduring. There was no epiphany, no rebirth, just resignation to enduring another day. It was, in some ways, unforgivable surrender. I must have too dead to die.

In London, twelve months later, I found her. I saw her before me, grinning wryly in the shadow of the city, and something awoke in me that I could not name—something fierce, like defiance, and rapturous, like joy. I knew then what I should have known all along: that no minor circumstance of my wretched world could have undone such a mind. How arrogant I had been, how misguided, to imagine that I alone would crawl back from a self-appointed grave. Denied the solace that I owed her, she had endured. I had betrayed her entirely, I had failed her unforgivably—but still, she had come back to me, and she was altered but alive.

We spent six hours in a dimly lit bar. A part of us had died with bygone days. We both felt the irrevocable absence, both mourned what we could not change, but we spoke on in spite of it. Until my mind fails me, and perhaps even then, I will remember that night. How natural it felt to be one with her again. How readily I knew her mind, and no wonder—it was, after all, mine.

The bus was silent and midnight was long past. From one sleeping city to the next, I rode with leaden eyelids and an opiated soul. The man sitting behind me took a call on his phone, and received, as I could perceive it, the news of a someone’s death. Someone he had loved, at some time and in some fashion. I could it hear it in the way his voice broke, running like a wrist across the edge of each word. I lapsed in and out of consciousness. He bled as he spoke.

There I was, on a night already torn with strange twists of circumstance, a voyeur to someone else’s tragedy. While some part of me felt deeply for him, it was more than I could communicate or understand. I thought of her, the catastrophe that almost was, flooding exhausted memory in white roses and sightless eyes. It was all so simple and so very strange—how do bodies die? And why couldn’t ours, when we wanted them to?

Sometimes I wonder at my own existence. In my emaciated, Orphean state, I can see the subtle movements of the bones beneath my skin. After all of these years, I am nourishing myself still.

I will always remember you fondly—those nights of shared cigarettes and endless conversation, your unconscious earnestness and easy laugh, how sweet it felt when you finally kissed me on the corner of that silent street. In some ways you are so very like me. You are suffering, you are not whole. On a bridge above the nighttime currents of the Thames, for a handful of five-pound notes and a few quiet words, you gave me consecration in its chemical form: that folded piece of paper, so small and nondescript, that would undo us both in time. You ran your hands through my shaved hair, along the lines of ink that moved over my skin like the waters below us, and for an instant I was exquisitely aware of my own living form. In some ways, I think I always knew you. I think you have always wanted to be known.

But I cannot remain in stasis any longer. I cannot limit the potential of this body and its longings. Just the other evening, I learned the language of another form that was not yours, I brought myself to life again in each rapid breath he drew, in the mouth that moved beneath my fingers, in the dampness between my thighs. I took him apart with my teeth, chose to suffer so I might heal—and how wonderful it was, to feel those muscles move again. Entwined in his limbs, I lay waiting for the morning. I watched a cold light fall across the bruises on his shoulders, over the places where my teeth had left impressions in the skin.

This is how it always begins. I have a beautiful, damning habit of loving many people—loving them deeply, ardently, differently, and all at once. Even now, I have not forgotten you. There are still so many ways in which I wish I understood you, so many questions I never thought to ask. Are you lonely in the winter? Are you afraid to die?

Maybe, in time, you will overcome what has happened to you, and awake some morning to find that you are whole and strong and ready to try again. It will have to be with someone else. You have suffered enough, my love, but so have I.

Allow me leave at last, to live indifferently on—and until the night comes howling, may I never write of you again.

For my mother, who knows who she is.

Alison Bechdel, Are You My Mother?

I recently had the pleasure of working with Corinne Singer and Maggie Kobelski on Corinne’s ongoing series in feminist self-portraiture. The first installment, entitled “Mother, May I?,” came into being in December when we wen visited a seaside town where I had spent my childhood summers, and I walked into the Atlantic in my mother’s wedding gown.

For as long as I can remember, it has been expected that I would marry in that dress, but in the wake of the deterioration of my parents’ relationship, my struggles with mental illness, and my efforts to come to terms with my own sexual and gender identity, the implications of such an assumption took on less welcome significance. Always vaguely symbolic of conformity, by the time of the shoot, my mother’s wedding dress had become a representative site upon which the traumas of my adolescence—the constraints of heteronormativity, the lingering anxiety of disappointing my parents—were made manifest.

In many ways, “Mother, May I?” was a challenge to my own body. Kneeling in ivory satin in the frigid water was a means through which to explore my own physical limitations. The entire endeavor can be read as a reflexive, even masochistic act.

The themes we discussed before the shoot were captivity, sacrifice, abandonment, solitude, desire, subjugation, shame, self-medication, rebellion, baptism and rebirth. I I have rarely achieved the sense of catharsis that I experienced modeling for this piece.

This narrative is dedicated to my parents, my queerness, my body, my self. It is dedicated, in short, to the willful destruction of beautiful things.

1. Surrounded by containers of makeup, clad from the waist down in my mother’s dress, I face a mirror imbued with my form. Although it was originally intended as a test shot, I begin to view this photograph, the first in the series, with uncertainty, and then fascination. It is strange to see my own image, twice framed. In this effort towards self-portraiture, I am the object of my own contemplation: the project begins, as it likely should, with the ongoing question of my gender, and the conscious performance of a self.

2. Kneeling in the sand for carefully constructed evocations of wedding photographs, the first thing I am conscious of is being colder than I could have imagined. The dress, which encompassed my mother’s form so gracefully when she was only 25, is too large for me: reams of white satin drape awkwardly over my angular frame. My lips are ashen, almost anemic. They echo the landscape around me.

3. These are the photographs that my mother dreamed of seeing when she gave birth to me, her only daughter. But like the dress, they do not fit. They are unsettling. Discontent textures each image. Is this only permissible way for a body to fill the space that surrounds it: as the object of another’s gaze?

I cannot be adequately represented, or even contained, by those sterile, bloodless images of a woman that I am not. The the tide advances. I move towards it. I anoint my face with sand and salt water. My makeup runs in rivulets, my hands claw at the earth. I am abject and full of rage. Rage for my mother’s abandonment, rage for my own mutilation: those years of self-loathing that that made me what I am. My entire body reacts against the fact that I was given so little say in what I would be expected to suffer and survive as a woman, as queer, as fatherless, as alive.

Something strange and sorrowful and maddeningly close to beauty lingers in the fading light.

Perpetually in conflict with this slowly dying body, smoking is a habit I engage in because it allows me to remain as sane as I am capable of feeling. It is an addiction born of trauma, which has nevertheless become my own. I can claim each breath I draw, pretend not to care about the choices I have made, even as they consume me. This is my reaction to a culture that reprimands self-medication without considering its origins or the consequences of its absence. After all of the ways in which I have been undone, here, at last, is a damage I inflict upon myself.

By the time the cigarette has consumed itself, burning away into ash, I am too cold to feel my skin, but my pulse is more realized than ever. The dress has been torn and cut away, baring my skin and its many strange desires. There is a primitive, almost feral element to my defiance.

Despite all of my bitterness and my retroactive grief, it is a mournful and lovely thing, to lay waste to the dress my mother thought to see me married in. The fabric is still beautiful, even in its ruined state, as I kneel beneath a radiant sky. It feels like a baptism, to immerse wholly in the currents, to reckon unflinchingly with the girl I was, the person I am, whatever I am to become. Is this what it feels like to finally begin to heal?

Maybe—but then again, maybe not. In spite of whatever language or meaning I impose upon it, the story the fabric tells is simple. I need a new beginning. I think I always will. But on the shorelines of my childhood, and in the object of my eternal fascination, the sea, I try for the next best thing.

Amid those timeless waters, I evoke the sensation of being reborn.

Oh, my love, take me there.

Let me dwell where you are.

I am already nothing.

I am already burning.Sophocles, Electra

Mild December mornings find me listless and on edge, smoking and drinking weak coffee in East Village. Listening to jukebox pop songs, avoiding street cabs and strangers’ eyes, I adjust to the insincerity of the city, immersed all the while in the dim paranoia that colors an insomniac’s reintegration into the waking world.

There are always days or weeks or months, impermanent instances wherein I begin to wonder whether or not I have lost my mind. Every time, I worry that I will not recover, that this time, it is for real. There is a certain joy in the recklessness with which I navigate these temporary bouts of insanity. Cynical and strangely high-spirited, quick to laugh and slow to focus, I live like an exposed nerve.

I am always between worlds, haunted by the specter of displacement that strays through each new city at my side. I long for home, return to realize that it was never really there to begin with. I spend the holidays reliving each whiskey-dimmed wandering down silent streets in England, recalling the directionless respite where my second life lies.

Just the other day, my and friend I decided that we had witnessed enough, and we drove four hours north down a narrow highway until we reached an empty town at the edge of the Atlantic. T We quoted half-remembered lines of poetry, rewriting the margins of measurable time, and we returned home again in a haze of joyful abandon: driving too fast, shouting the lyrics to old songs as they rang from the broken-down radio. Sometimes I have nights like those, and I realize that it is not so terrible to live, to think, to feel. I remember that I have the constancy and love to form relationships that endure. I find solace within, and in spite of, a world that offers none. I live on, and on, and on.

I attribute my sexuality, my singular and self-contradictory identity, in large part to the fact that I am crawling out of my skin with fascination for the bodies of others. I do not accept the politics of compulsory heterosexuality. I am too passionate, too desirous, too curious, too undone. I refuse to limit my experiences to any one gender. I want to be young and half-mad forever.

There are times when I feel exhausted. Is it possible to reckon with the impulse of our histories without feeling older than we are? It might not be so tiresome if I could see the dimming years as inconsequential: if I could allow past lives, and loves, and losses to fade away into obscurity. But I have never known how to lie to myself.

Sometimes it just doesn’t work. Sorrows that are the most insurmountable, the most exquisitely damning, are always conflicts of positioning. Sometimes someone gives you everything they have to offer, and it still is not enough. The timing is wrong, your body is wrong, you need something that no one can give to you. And it makes you happy and sad at the same time: because you know you are as content as you can be, and you realize that maybe you will always feel this way, and you wonder why life, at its best, still feels this way.

How can I explain to those that love me, that remembering them is like catching smoke in my fingers? Nothing is sacred, not anymore. Every time I start again, another person, another place, it ends with the same banal sentiments: I want you to know that I really did love you. That I really did try. Self-preservation becomes its own form of cannibalization. I lend my mind to intrigued strangers, and forget them all just as easily. Why have I allowed myself to become this way?

In those rare moments when I am fully present, I find comfort in feeling deeply: in eclipsing all that another has to give. How many times have I lived over that scene, enthralled by the futility of our efforts? Two uncertain strangers, afraid of our own desires, sharing nothing but that sense of fascination: intrigued by one another, by ourselves. Satiating nameless needs in rough acts of tenderness. You asked me to stay, pushed my hair out of my eyes—and what a choice I made that night. You will never really know the courage and carelessness it took.

In the weeks that followed, I dreamed vividly of a different place. There were asphodel petals and juniper branches, and mirrors imbued with light. You were there with me, your words tinged inexplicably with remorse. I understood you then, as I never have before or since; your clandestine sorrow, the hushed apologies when you took my fingers in your mouth. I felt the rhythm of your throat, the murmur of your heart beneath my hands. How lucky I am to have found, in this absurd existence, such wonderful ways of passing the unwanted time.

An absence bleeds within and throughout you, coloring your countenance like memory running through a living mind. Once, and never since, you gave that absence living form, reminding me of one who, in another time and place, did the very same. Hers was the body from which I learned my love and limitations. Is it so surprising, then, that I reacted as I did?

I will not love you, but I like to know that I can, and that I would heal you, if I could. I give this potentiality less threatening form through a detached curiosity: could I bring a person such ecstasy, evoke such adoration, that they never wanted to leave? I have been left all my life. I seek respite in these urges, but reject the thrall of fixation. I have too much to think of, too many things to create.

I turned once more, in your case, to the confines of my mind. False remembrance served as my means of forgetting: I approached the construction of your form as I might an exorcism. You bled from my hands onto the page, leaving charcoal stains on my fingertips, my wrists, the skin on my forehead where I pushed the hair back into place. Everything I touched, I marred as though with ash.

I chose the wrong person again. I always do. But then, don’t we all? And what does it matter anyways, when a thousand forms and figures pass through my periphery? Even now, another soon-to-be memory strolls through the shops and alleyways of the city, evoking all of the opportunities I never took. In the morning, her name is everywhere: it floods my mind in a thousand strains of music, running like rain through the streets.

When I write too often, it all starts to feel the same. I knew you, I loved you, and I will remember you. What a strange and terrible thought it is, that I may wake tomorrow feeling nothing at all.

But fuck that, fuck all of it—I have too much left to write about. I am alive now, and two years ago that is more than I could have hoped for. I write for myself now, because in this senseless reality, I am my own best subject. I refuse to be remorseful, to water down my existence to self-effacement and apologies. Why be selfless where you can be satisfied? Everyone is surviving something, after all. I am not even sure what it really is that I write about now. My hands shake with a thousand unnamed longings, but I am not suffering, not anymore. I do not want to die: I burn and burn and burn. This is what I am now, this is where I stand. It is precarious, it is absurd—but I love it, all the same.

Were you exasperated and disgusted by her, as an extreme form of yourself? Your wild talk, your turbulent moods, your ‘dark places’? Mental illness frightens you, like a contagion.

Joyce Carol Oates

To watch me love another is to gain insight into the many ways in which I may still hate myself. I am reckless. I am desperate. I am provocative. I am extreme.

I know a capacity to give myself away that transcends age, gender, circumstance. I impale myself on every detail. I feel everything. I have to. Why else would I climb each cross so willingly?

Underneath it all, in the secret cores of our cowering souls, we all crave subjugation. I dread every new morning, every glance in the mirror, my own chastising gaze. I navigate convoluted prisms of desire, performativity, and shame. What new horror have I inflicted on myself? What will I have to live with today?

This is the litany of a violent soul in stasis and a mind only slightly unhinged. With no circumstantial catastrophe to engage it, such energy devours itself. Unexpectedly, but not inexplicably, I am reckoning with a conscience I always thought I understood. My work is antithetical to my sanity. My art is in conflict with my self.

I must live within a language that is no longer my own. Something ancient and sacred was taken from me. Rhythms and rituals recall what I am—and what I am is a neurotic, in the most organic sense, never adjusted to this world, forever adjusted to myself. I want to be open. I want pleasure and tenderness and melancholic sin. I crave ecstasy, and when this life offers less of that than I can endure, I engage in relentless self-consumption. I am satisfied and insatiable, drenched in a desirous impulse.

How can anyone experience an entire existence, so vast and mercurial, through a single body? The inimitable allure of literature and of music in the streets, the sheer stimulation of these people and this place. Self-mutilation is almost a memory now—but in moments of almost unendurable ecstasy, I imagine that if I were to open my own skin once more, my inner self would be revealed not in crimson drops, but in radiant prisms of light.

I will never love anyone the way I loved my father. No one will ever love me the way my mother has. Some people are intrigued by what I present to them: they want to interrogate it, engage with it. But who would ever stay? What person could reckon, willingly, with the violence of what I am? At the extreme risk of self-debasement, I engage wholly with my own impulses. If I do not take myself seriously, who else will or can?

In this respect, I am a narcissist. It is not the person that matters to me, but the figure: its relevance, its calibration within my life. My egoism is empathetic: my love is rapid and deep, but directionless. I cannot yet (or can no longer) emulate that mature adoration that constitutes a stable ideal. I cannot always feel this way. I will forget this sensation, but will remember experiencing it. And then I will forget that too: my present self will be explicable, but not justifiable, to whatever I become.

In the ardent haze of summer, I knew an artist who painted a piece about womanhood, about ecstasy, about me. Across the top she wrote “Always,” and being who I am, I believed it. Sometimes I still do.

But just months later, I wandered streets slick with rainwater and lamplight, with a man whose deep-set eyes were the exact color of the morning. I awoke to glass windowpanes slick with frost, and my clothes were strewn across the painting, which lay on the floor where I had left it unfurled. I look at the soft, stained fabrics that belonged to me. The delicate lace was precisely the same shade of crimson as those tenderly bleeding words. Always. Beside me, another body was sleeping soundly, breathing softly, knowing little, caring less. Always.

That dispersion of paint across canvas, that memory of such passionate desire, seemed strangely at odds now with the cast-off clothes of the person it had memorialized, and the young man now asleep in her bed. It was pretentious, it was absurd, but for a moment I felt older. Like I had lived and loved a lifetime’s worth. I felt tired and I felt alive. For a moment, I could not see her as clearly. I could not recall the exact color of her eyes.

It fades. It always fades. All I ever need is another figure, another body, another site of imposition for the discursive interest that colors my mind. I pace the silence at the edge of my bed until I hear my name drop softly from another’s lips. It is as beautiful as it is damning. I remember every person that I meet.

Spires dream but I am awake with the morning. The cobblestone streets of the city settle in the contours of my soul.

I am growing, changing, becoming. I feel too deeply. No body can contain me. I cannot be alone, not ever. Except that I already am. I always have been. I consume—and so doing, nourish—myself.

The sun had not yet fully risen when I locked the bathroom door behind me and looked hard at my reflection in the mirror. His breathing fell like rain against windowpanes, echoing in my skin. I stared at the girl standing before me, and there was nothing to do but wonder what the hell had happened to her, and when.

Recent Comments